Die Zauberflöte at Deutsche Oper Berlin

This opera is an excellent case study of how social conventions have evolved over the past 233 years since its first performance, when gender roles, understandings of love and marriage, and authority in general were understood vastly differently from what we have (more or less) agreed upon today.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

🎭 Die Zauberflöte

🎶 W. A. Mozart

🏛️ Deutsche Oper Berlin

🗓️ 15.09.2024

When seeing Mozart‘s Zauberflöte, you‘re really watching two operas in one. At its surface, the opera tells a straightforward fairytale story of wild beasts, magical instruments, good and evil, feathered humans, princes and queens. This “superficial” story is also what understandably makes the Zauberflöte so attractive for kids (of which there were plenty in the audience—what a delight to hear a giggle every now and then). Underneath, however, lies a gripping plot which I believe makes this opera one of the most fascinatingly complex and paradoxical in the entire canon.

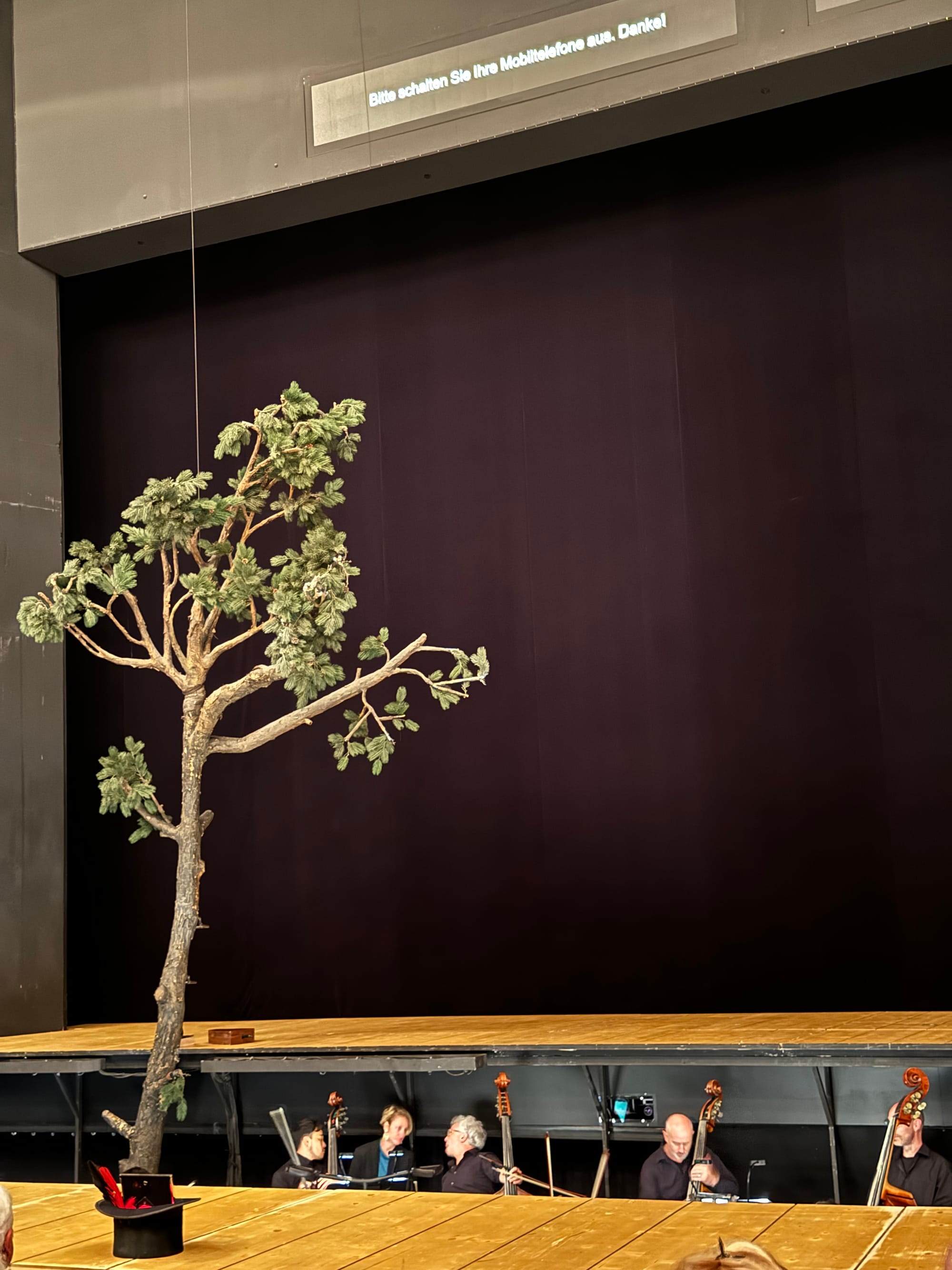

The production at Deutsche Oper Berlin does a fantastic job of telling both stories at once. The 1991 stage design is simple, but visually striking, with contrasts of light and color metaphorically visualizing the plot’s dominant conflicts, all the while having clever set transitions, up-close-and-personal action in a walkway between audience and orchestra, and a pretty convincing snake/dragon/monster in the first act.

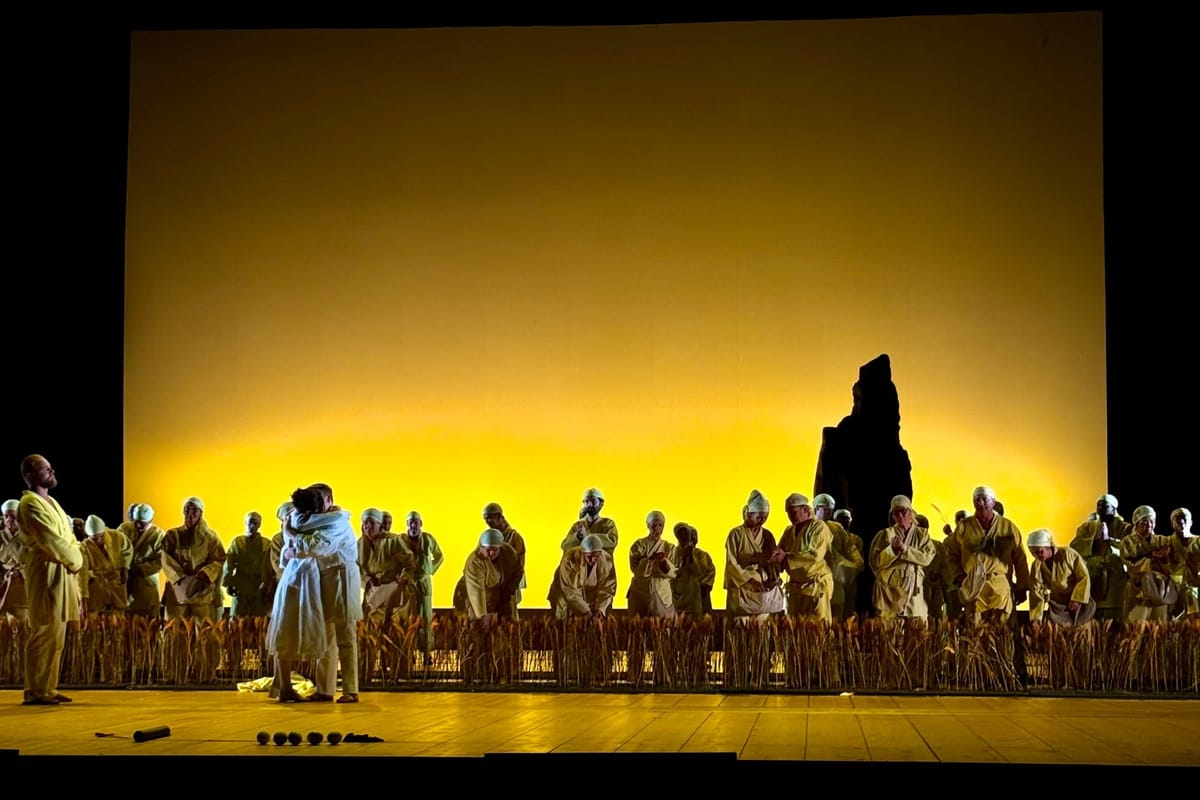

Central to the opera are opposing narratives which shape how characters perceive reality and how they act in it. On one side, the distraught Queen of the Night’s daughter is violently kidnapped by a demon ruler and requires saving by the prince. On the other side, a benevolent leader saves Pamina from darkness and ignorance, and grants her eternal happiness and wisdom with a prince on her side. In a way, both of them are truthful, and yet this conflict is never resolved, leaving the audience to pick sides—although ultimately, it seems like Sarastro’s narrative gains the upper hand and the opera has a “happy ending”, literally in a golden sun-soaked field of wheat. In the post-factual world we inhabit, this narrative vs. narrative dynamic is unsettlingly topical.

Beyond this monarchic power play, the Zauberflöte is an excellent case study of how social conventions have evolved over the past 233 years since its first performance, when gender roles, understandings of love and marriage, and authority in general were understood vastly differently from what we have (more or less) agreed upon today. It is therefore interesting how modern sociocultural conventions have prompted revisions in the libretto to reflect these changes. Mentions of race (“black” vs. “white”) are completely removed, the slaves become servants or simply “people”, and one “M-word” is replaced by another (“Mohr”/“Mensch”).

The plot benefits from these linguistic changes: Monostatos, in the original a stereotypically racialized scapegoat, is given depth and ambivalence. His character is fleshed out and disentangled from a singular characteristic (his skin color), and his development instead centers his humanity (“der böse Mensch”). This human focus is curiously in line with Sarastro’s famous description of Tamino: he is first and foremost human, and prince only second.

Despite such linguistic revisions, the Zauberflöte is very clear about its historic gender roles, the position of women, and its strictly heteronormative conception of partnership (“Mann und Weib, Weib und Mann”; unsurprising for 1791). Women have a duty to please men (“Ist der Weiber erste Pflicht”) and must prove their worth to be part of community (“Ist würdig, und wird eingeweiht”). While men must also overcome challenges, the trials that Tamino and Papageno face in this production remind less of freemason rituals, and more of college hazing initiations. Love is also understood in a gendered way: For women, love comes caringly from the heart (“Würd’ ich mein Herz der Liebe weih’n”), while Papageno would prefer to own and lock up ALL girls and women.

With this complexity in characters, motivations, and conventions, it is almost paradoxical that the Zauberflöte appears to offer such unambiguous moral guidelines of good and evil, consistently praising innocence, wisdom, fortitude, and honesty as virtuous—and painting a clear picture about who adheres to these values. Spoiler: with the exception of Pamina (who works her butt off for this recognition), only men possess these qualities. And it is ultimately Sarastro who grants approval while claiming moral superiority. Ironically, the production introduces him as “primus inter pares” emerging from field work, while his subjects praise him as their “idol”. And because the German “Abgott” has an almost divine Sumerian connotation, I’m getting Maoist agrarian cult vibes from Sarastro and his (oppressed?) followers.

Regardless of what Mozart and Schikaneder intended (re: discourse “were they misogynists or not”), it’s about how we read and perceive the social dynamics offered by a historical piece of music in a contemporary setting. And, true to every piece of art, each participant and observer will have their own thoughts and interpretations of the plot and its characters. And yet, one thing we could hope for when glancing into our sociopolitical landscape is for one ideal of the Zauberflöte to become reality: “Bekämen doch die Lügner alle ein solches Schloss vor ihren Mund; Statt Hass, Verleumdung, schwarzer Galle, bestünde Lieb und Bruderbund.” <3

On a final and more personal note, seeing Die Zauberflöte is a particularly emotional experience for me, every time. In my „first career“, I sang at the @aureliussaengerknabencalw boy‘s choir essentially full-time for years, and had the privilege of singing the Erster Knabe a handful of times at the operas in Bonn and Frankfurt. This is now almost 20 years ago—talk about past lives!