Nosferatu at Babylon Berlin

The live music accompaniment is essential, breathing new life into the sometimes glacial pacing of silent cinema. It keeps the audience engaged and heightens appreciation for this form of musical art—something that can lost in films from our time.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

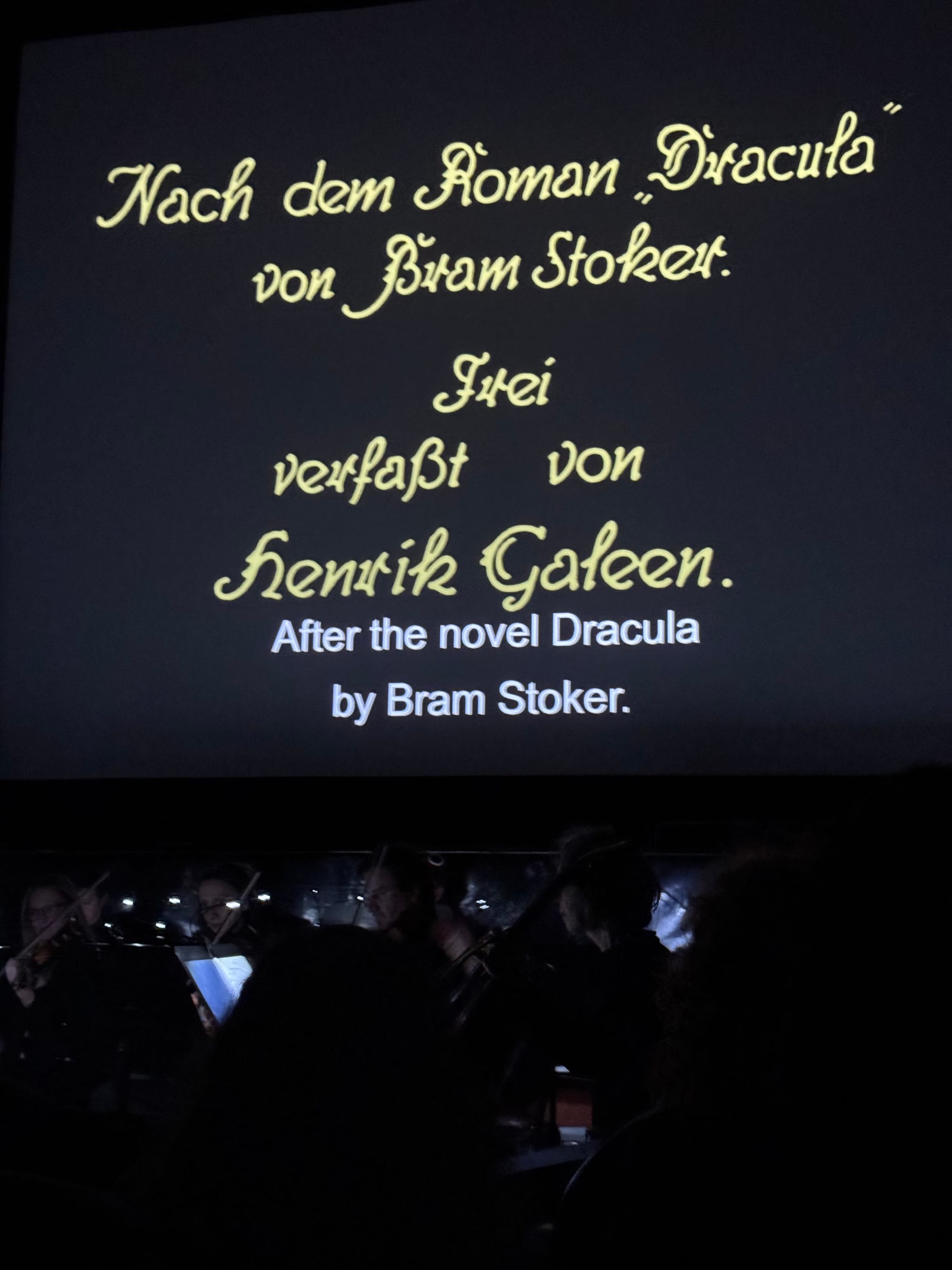

🎭 Nosferatu—A Symphony of Horror

🎶 Hans Erdmann / Hans Brandner

🎥 Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, 1922

🏛️ Babylon Berlin

🗓️ 28.12.2024

A visit to Babylon Berlin is like a journey back in time. From the New Objectivity architecture to the live music accompaniment and Germany’s only full-time cinema organist, BABYLON immerses its audience in the bygone era of Weimar cinema (how exciting to have some current political parallels as well!). Watching the 1922 silent film classic NOSFERATU with a live orchestra (Babylon Orchester Berlin) only reinforces this sense of time travel. F.W. Murnau’s icon is THE prototypical horror movie, foundational to the genre, and a cornerstone of early cinema in general.

Both the movie’s score and tagline (“Symphony of Horror”) accentuate the close connection between silent film, symphonic composition, and opera. The movie is structured into five “Acts”, while the score—titled a “fantastic-romantic suite”—is divided into ten evocative movements, each capturing a distinct mood and titled with what we might today call a ~vibe~: Idyllisch, Lyrisch, Spukhaft, Stürmisch, Vernichtet, Wohlauf, Seltsam, Grotesk, Entfesselt und Verstört. Though much of the original score has been lost, Babylon’s version is a meticulous reconstruction, offering a faithful tribute to the film’s musical heritage.

The live music is essential, breathing new life into the sometimes glacial pacing of silent cinema. It keeps the audience engaged and heightens appreciation for this form of musical art—something that can lost in films from our time. The orchestra doesn’t just accompany the film; it transforms it, turning each scene into a visceral operatic experience.

Interestingly, but not entirely unexpectedly, the modern audience responds quite differently to Nosferatu’s “horror” than viewers in 1922 might have. In quite a few poignant scenes, there was laughter instead of gasps of horror. To be fair, some early critics already noted that Count Orlok wasn’t particularly terrifying, with a too brightly lit presence. And yet today, the godfather of modern vampires (no Edward without Orlok) verges on camp—complete with sexual and homoerotic undertones (perhaps unsurprising given that Murnau was a fellow gay).

Additionally, the film gives us valuable insights into the time of its production, as well as how Germans of the 1920s viewed their own culture roughly 70 years before. Having been filmed in real locations instead of sound stages—unusual in German cinema at the time—the movie captures hauntingly beautiful images of cities like Wismar, Lübeck, and Rostock before their destruction in World War II. It also offers a romanticized view of mid-19th-century Biedermeier ideals: private domesticity, idyllic landscapes, and rigid gender roles (perhaps “ein zu weites Feld” for this post).

With the 2024 remake of NOSFERATU on the horizon—its trailer already full of references to the century-old original—there couldn’t be a better time to revisit this silent masterpiece. At Babylon, NOSFERATU is more than a film; it’s a vivid bridge between past and present, cinema and music—and, if I may, remains a camp, queer icon. Slay!