Rusalka at Staatsoper Stuttgart

A bold reimagining of RUSALKA, this production transforms Dvořák’s opera into a dazzling celebration of drag and queer resilience. Blurring boundaries between worlds, it challenges norms, subverts tragedy, and reflects our own relationship with identity, beauty, and belonging.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️/4

🎭 Rusalka

🎶 Antonín Dvořák

💭 Bastian Kraft, 2022

🏛️ Staatsoper Stuttgart

🗓️ 22.03.2025

“NEITHER ALIVE NOR DEAD, NEITHER WOMAN NOR NYMPH”

RUSALKA at Staatsoper Stuttgart is not just a retelling of the classic fairytale—it is a bold reimagining that transforms the opera into a celebration of queer excellence and drag culture. Dvořák’s tragic water nymph tale, traditionally a melancholic reflection on love and loss, is here reframed as a story of identity, self-acceptance, and resistance to binary norms. The result is as moving as it is cunty—a word I wasn’t expecting to use in an opera review, but one that is entirely fitting in this subcultural context. This production retains the mermaid essence of the original but subverts it, using drag as a powerful medium to explore queerness and otherness. From the first moments of the opera, this motif is woven throughout the storytelling, sometimes subtly, sometimes in dazzling, unmistakable ways.

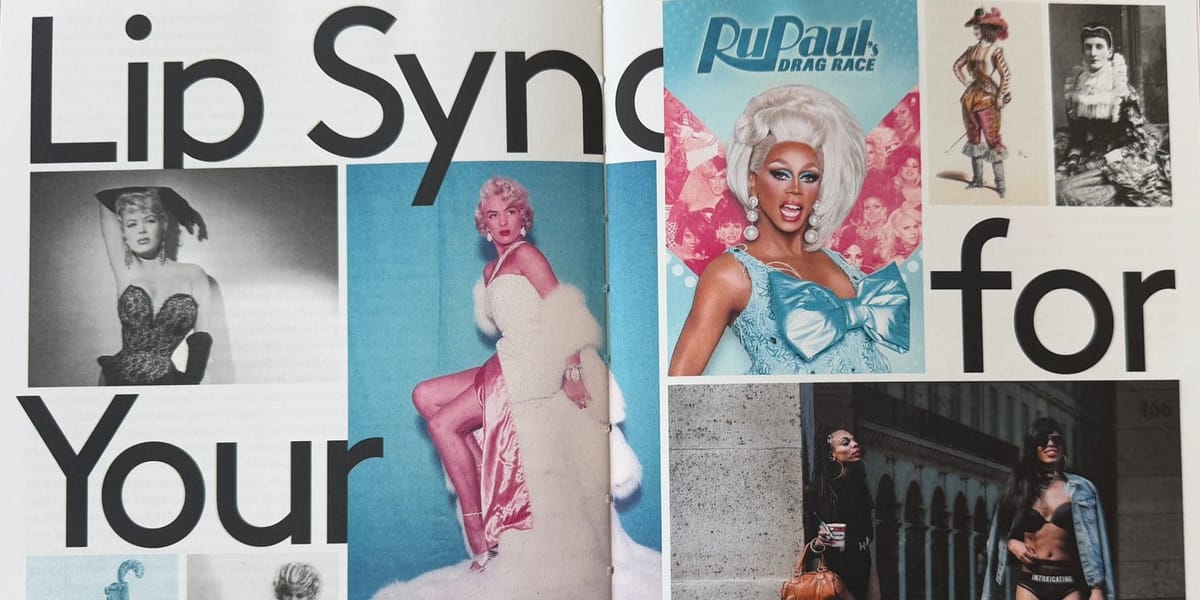

The production: a lip sync for your life

What makes this production so unique is its double casting of certain roles. All inhabitants of the mystical nymph world are portrayed not only by singers but also by drag queens who embody them physically onstage. The visual impact is stunning: the stage itself becomes a living lip sync performance, reminiscent of a grand finale of the global phenomenon of RuPaul's Drag Race. Yet, in this case, the challenge is not among the drag queens themselves but between them and the human world—a world that refuses to accept them. The nymphs become an unmistakable symbol of otherness, standing in stark contrast to “the human world,” which in turn represents the dominant heteronormative and binary society.

Within this lip sync dynamic, it is actually the drag queens who take center stage, while the singers provide the voices they perform to. Initially, these two worlds remain separate, clearly divided by the stage design: the singers reside in the “human” realm, positioned on a walkway high above the stage, while the nymphs occupy the “underworld” below (Rusalka will later be banished “back to hell”). A vertical ladder connects these two spaces. As the singers perform above, their drag counterparts act out the plot below, in typically grand, dramatic lip sync fashion. The connection between singer and queen is cleverly reinforced through color-coded costumes, the choreography of their mirrored movements, and the striking precision of the lip sync itself—an impressive feat, considering the opera is two and a half hours long, and in Czech no less.

Mirroring itself is a central theme of the opera, reflected both in performance and staging. A massive mirror, spanning the entire length of the stage and fixed at roughly a 45-degree angle, allows the audience to see the drag performance from multiple perspectives—both front-facing and from above. The effect is uncanny: it’s as if we are peering directly into the nymphs’ watery world. The oscillating surface of the mirror further enhances this illusion, evoking the rippling of a pond. Yet this bold staging choice also creates a fragmented visual experience; at times overwhelming, as the audience must navigate three frames of reference—four, if we include the libretto supertitles: 1/ the “human” walkway on which the singers perform, 2/ the stage level where the drag queens bring the story to life, and 3/ in between the two, the mirrored top-down perspective of the second. Conversely, even though the stage mostly consists of black background, it appears filled to the brim with life and color.

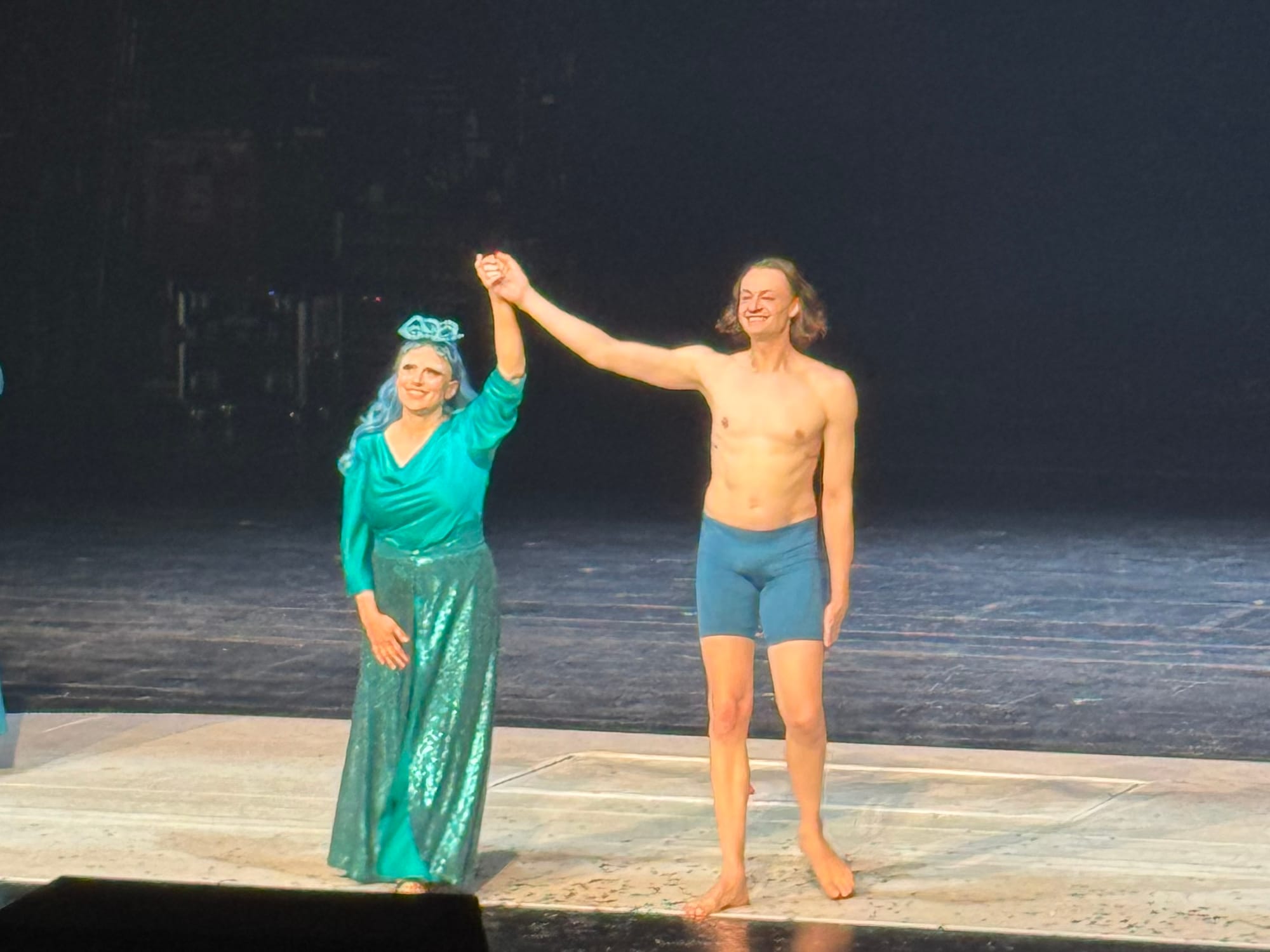

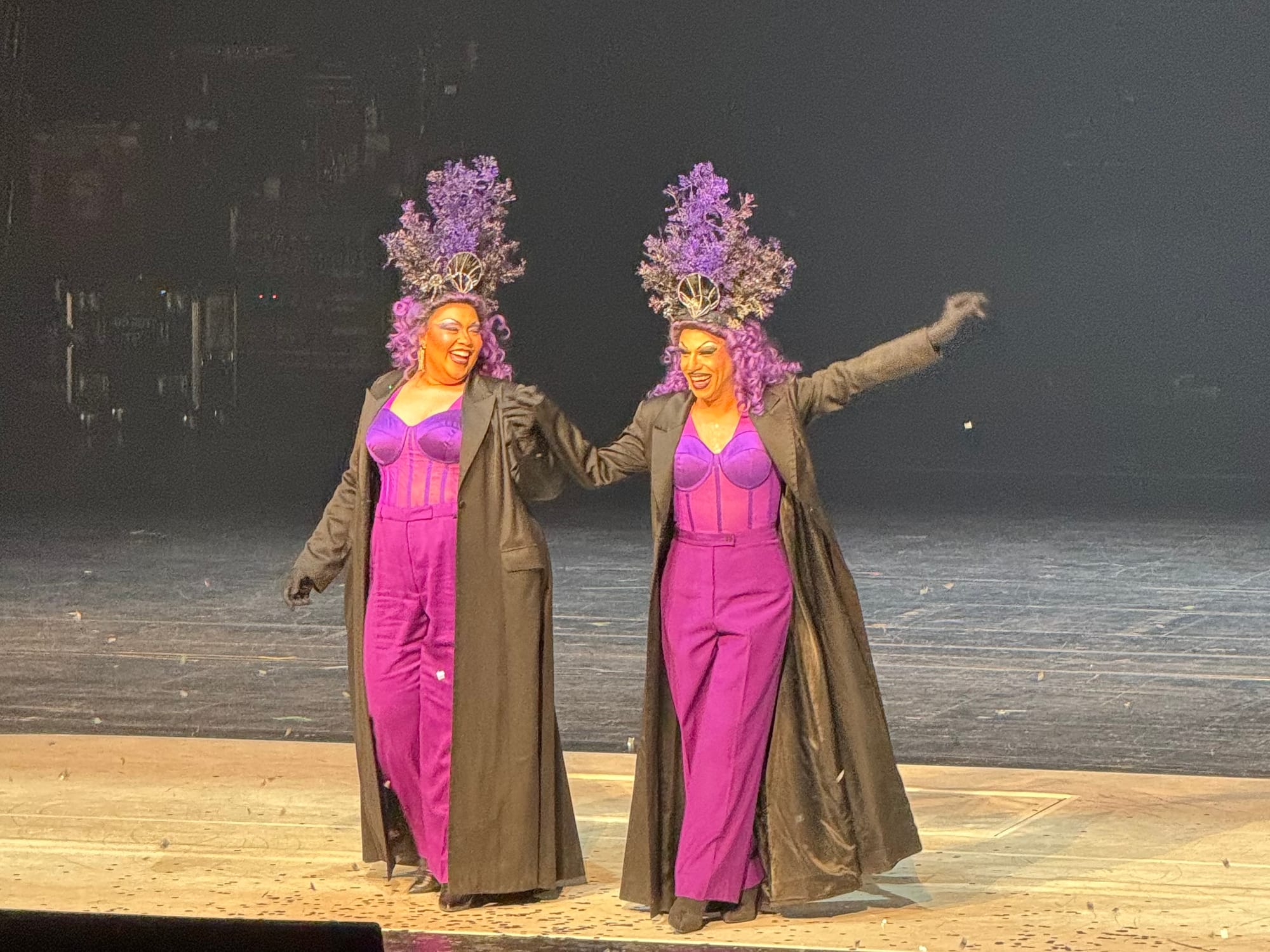

As the story unfolds, the relationship between the drag queens and their respective singers evolves. Initially distant, the two worlds collide dramatically when Rusalka undergoes her transformation from nymph to woman. In this pivotal moment, the singers descend into the watery realm, directly interacting with their drag counterparts for the first time. The visual language of this transformation is deeply reminiscent of Disney’s The Little Mermaid—but with a twist. The Jezibabas, dressed in rich purple hues evocative of queer icon Ursula, cast their spell around Rusalka. Of course, Ursula herself was famously inspired by 1970s drag legend Divine, creating yet another layer of queer lineage within the performance. As the spell takes hold, Rusalka signs her name, sealing her fate—one we recognize from countless versions of this fairytale: if she cannot make the Prince love her, she will be doomed.

When the Prince finally meets Rusalka, the barrier between the singer and the drag queen dissolves entirely. The two merge into a single entity, their movements intertwined, almost as if one is puppeteering the other. And as Rusalka falls into silence, it is the drag queen who ascends to the human world, while the singer’s voice, for a moment, is no longer needed.

Queer acceptance: (still) a fairy tale?

The overture opens with a video projection that immediately sets the tone for the story. As the first notes of the opera sound, the stage is bathed in green-blue hues, revealing a bubbling underwater world that lulls us into its supernatural depths. Amidst the floating bubbles and darkness, a Barbie mermaid doll emerges, held by a young boy completely enthralled in his play. The moment is pure, joyful—until it is shattered. His father, face twisted in rage, snatches the doll away and hurls words at his son that, though unheard, can only be imagined as cruel. The stage is set: this RUSALKA is about the struggle for queer acceptance.

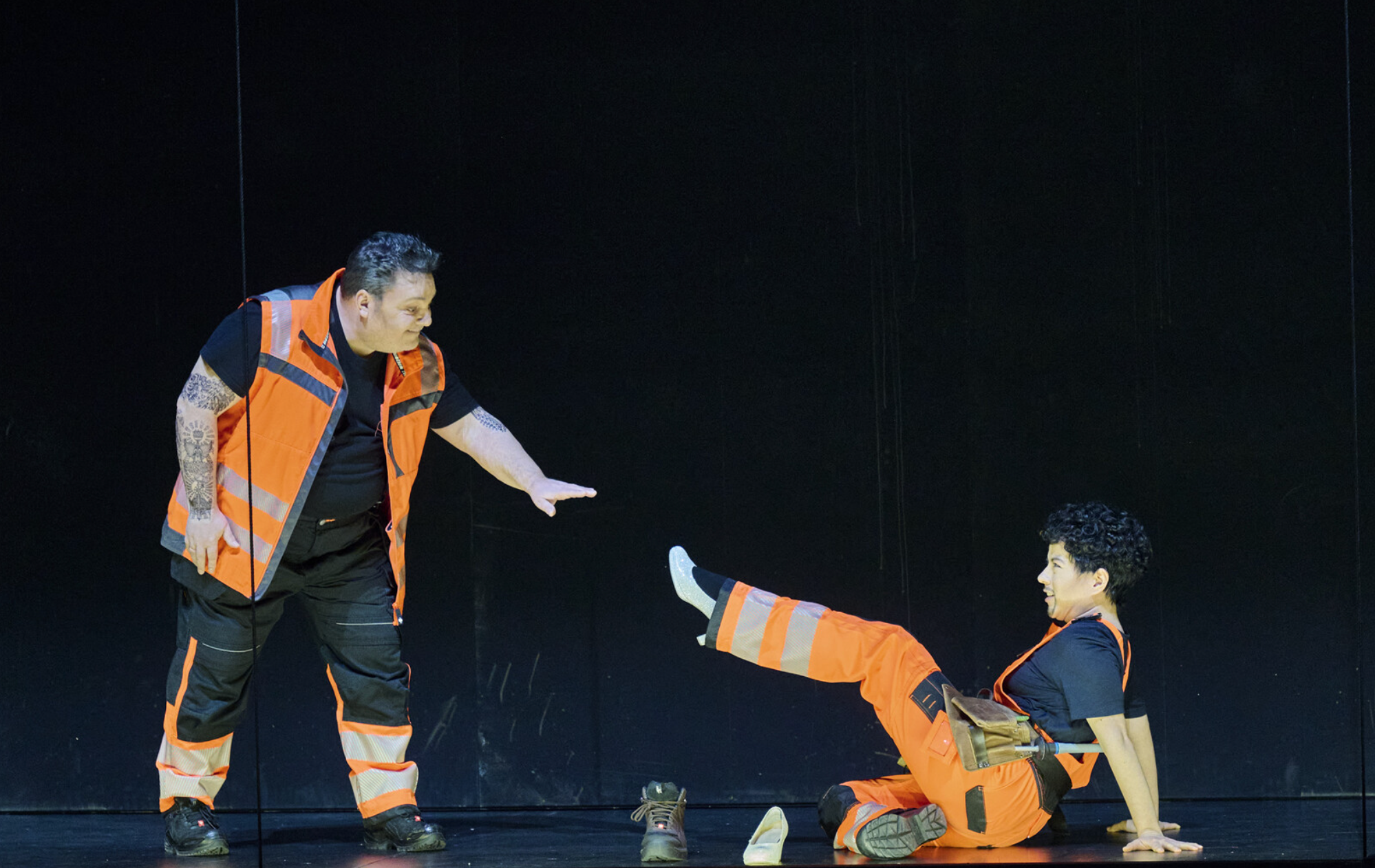

This theme resurfaces in Act III when the Game Keeper and Kitchen Boy—the latter visibly frightened—venture into the nymphs’ forest. Here, the words left unspoken in the overture film are finally voiced: “I’d be ashamed to be your father.” Earlier in Act II, the Kitchen Boy had briefly tried on a pair of off-white pumps, only to hurriedly cast them aside. The message is unmistakable: queerness and shame remain inextricably linked, and the struggle for unconditional acceptance is as urgent as ever. In a time of global retrenchment of queer rights, inclusivity, and diversity, RUSALKA's message feels even more critical today than when this production first premiered in 2022.

The production leans heavily into this motif, amplifying the tension between subculture and dominant culture. The nymphs’ realm is portrayed as a fierce, supportive sisterhood, while the human world is steeped in rigid heteronormative conventions. Nowhere is this contrast clearer than in the Act II ball, which unfolds as an exaggerated, hyper-gendered wedding ceremony. At center stage, a groom’s tuxedo and a bride’s dress stand as emblems of a strictly binary world order—an Adam-and-Eve construct that leaves no room for anyone who falls outside its limits. As the guests arrive, they instinctively divide into two separate lines according to gender, standing before their respective dressing room mirrors. Men straighten their collars and comb their hair, while women apply lipstick and adjust their hats, making last-minute gender-affirming refinements.

Rusalka’s presence disrupts this order entirely. Like a literal fish out of water, she flails across the stage, unmoored and unwelcome. Rejected by both women and men, she is met with hostility from all sides. It is no surprise, then, that the Prince ultimately chooses the human Princess. Though at first drawn to Rusalka’s otherness—fetishizing or romanticizing it—he discards her the moment he faces judgment and resistance from his peers. The warning embedded in the opera is clear: “Woe to those who encounter humans.” For anyone daring to defy social norms, this world is neither welcoming nor safe.

Queer resilience and self-empowerment

Conventionally, RUSALKA is a fairy tale with a tragic ending. Rejected by the Prince, Rusalka returns to her forest pond, both she and the Prince equally doomed by the spell’s curse. But in this production, with its moral compass guided by generations of queer resilience, Rusalka’s fate takes a different turn. Rather than tragedy, she finds peace—if not happiness. By the beginning of Act III, it is clear that drag is no longer just an art form but a culture, a way of life, a source of belonging. The “sub”culture has endured, remaining a home and safe space for Rusalka and her community. In an emotional transformation, the singers return to the stage fully adorned in drag, their dress, hair, and makeup now mirroring their drag counterparts.

One of the final scenes gives us a wholesome Drag Race Werk Room moment: the queens, now mentors, help the singers into their wigs, apply the finishing touches to their makeup, and prepare them as if for their next drag challenge. What once symbolized rigid gender conformity in Act II is now reclaimed as a joyful affirmation of individuality, artistry, and sisterhood. When the auditorium doors open, revealing an ethereal chorus singing from beyond, the significance of this moment is undeniable—it is sacred, triumphant, and absolute. The nymphs revel in their existence, declaring proudly: “I have a lovely little body,[…] it shines with its charm.”

With the final confirmation of the Prince’s betrayal, drag queen Rusalka takes a seat at a dressing table and begins a final act of transformation—one unlike any before. In an incredibly raw display of vulnerability, a camera above the mirror projecting her close-up onto a stage-filling screen, she slowly removes her wig, lashes, makeup, and contacts before finally undressing. With the Prince long dead, she ascends back into the human world. At first, it seems as though, in order to finally belong, she must erase everything that made her a drag queen—that her identity must be sacrificed to fit in. And yet, as the final notes play, the stage transforms once more. Suspended mid-air, Rusalka appears once again in the shimmering mermaid tail she first wore in Act I. The message is clear and deeply moving: her identity is non-negotiable, in or out of drag. This is not an act of surrender—it is a powerful moment of self-actualization.

This act of de-masking carries another layer of meaning. Not only does Rusalka, the character, shed her layers before the audience, but so does the drag queen portraying her. Many queens have described their onstage personas as a source of power and confidence—a form of self-expression they cannot always manifest in their everyday selves. To visibly transform from drag queen back to “mortal”, in front of an audience that likely has few other touchpoints to drag, is an act of remarkable vulnerability and resilience. Cue the standing ovation.

Outlook: what remains of queer “sub” culture?

Fashion has long demonstrated how subcultural trends evolve—starting as radical statements, then gradually absorbed into the mainstream, often losing their original defiant edge. Once a style is widely adopted, the subculture that created it must innovate, developing new ways to reclaim its identity and distinguish itself from a dominant culture that, more often than not, has been unaccepting or even oppressive. Take leather harnesses, for example: once a distinct marker of gay nightlife and fetish fashion, they have since been appropriated by straight club-goers and even paraded on high-fashion runways. Drag Race itself is following a similar trajectory. What began as a deeply queer, underground phenomenon has exploded into a global spectacle, reverberating far beyond its original camp subculture.

In this light, the merging of drag performance with opera feels like a double-edged sword. On one hand, it marks a major legitimization of queer culture—drag is no longer relegated to underground clubs but is now performed on one of the most prestigious opera stages in the country (though I’m happy to debate how “straight” opera really is, today and historically). A drag queen even performs from the once-exclusive royal box, a symbolic inversion of historical elitism. But on the other hand, much like queer fashion before it, what happens when drag is absorbed into the high-art establishment? Will drag need to reinvent itself yet again—not just as an art form, but as a tool of resistance? How can it retain its radical, activist spirit while shaping and challenging mainstream discourse? And how will local queens react—will they celebrate this Ritterschlag [knightly accolade] of the opera world, or resist it? Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive—there is ambivalence and nuance in this, too.

Personally, I choose to celebrate this RUSALKA. I attended the performance with my grandmother and two of her friends—all well into their 80s—and they were spellbound. As we discussed the double casting of Rusalka during intermission, one of them remarked with genuine enthusiasm: “It’s fantastic that they cast a man in this role!” For these three opera regulars, this RUSALKA was, in essence, their first authentic drag show. They might not be the typical audience for drag, yet this production left a profound impact on them—and on me as well.

Final thoughts

A particularly striking moment occurs when the on-stage mirror pivots, reflecting not only the performers but the entire audience. This clever use of the mirror seems to invite us to examine our own relationship with the “others”—those who challenge our norms, our ideas of beauty, and our understanding of queerness. As we see ourselves reflected on stage, we are forced to confront how we perceive the things that make us uncomfortable, that defy convention, and yet, in doing so, recognize how they can be sources of profound beauty and transformation. Now that is the power of drag!

Cast - 22.03.2025

Musical direction Luka Hauser

Production Bastian Kraft

Stage Peter Baur

Costume Jelena Miletić

Choreografy Judy LaDivina

Video Sophie Lux

Light Gerrit Jurda

Dramaturgy Franz-Erdmann Meyer-Herder

Choir Manuel Pujol

Prince Kai Kluge

Princess Diana Haller

Rusalka Esther Dierkes, Reflektra

Waterman Goran Jurić, Alexander Cameltoe

Ježibaba Katia Ledoux, Judy LaDivina

Gamekeeper Torsten Hofmann

Kitchen Boy Itzeli del Rosario

1. Elf Natasha Te Rupe Wilson, Vava Vilde

2. Elf Catriona Smith, Lola Rose

3. Elf Leia Lensing, Emily Island

A hunter Alberto Robert

Staatsorchester Stuttgart, Staatsopernchor Stuttgart